Setsuko’s Story: Life in Japan During WWII

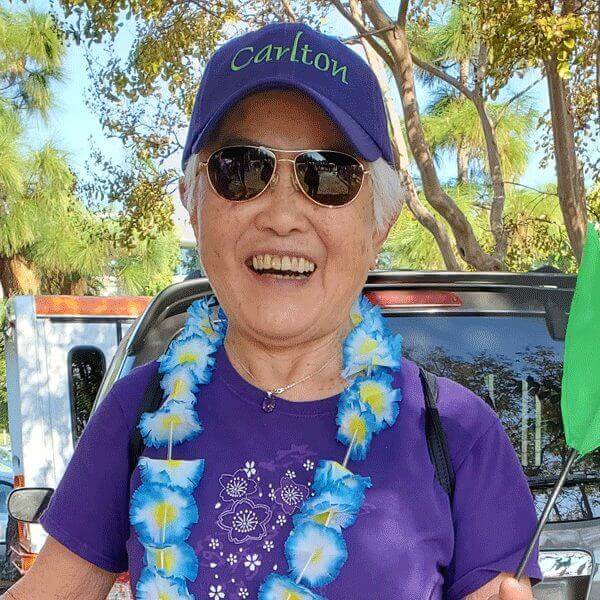

Written by Carlton resident, Harriett Burt, fellow resident, Setsuko, shares her story of life in Japan during WWII.

The oldest of five children, Setsuko Iwawaki was born in western Tokyo on February 20, 1929. In 1932 the family moved to downtown Tokyo, near the Imperial Palace and a large public park. Their home was not far from the Palace grounds which were open to the public twice a year. Also nearby was a beautiful large city park open to the public.

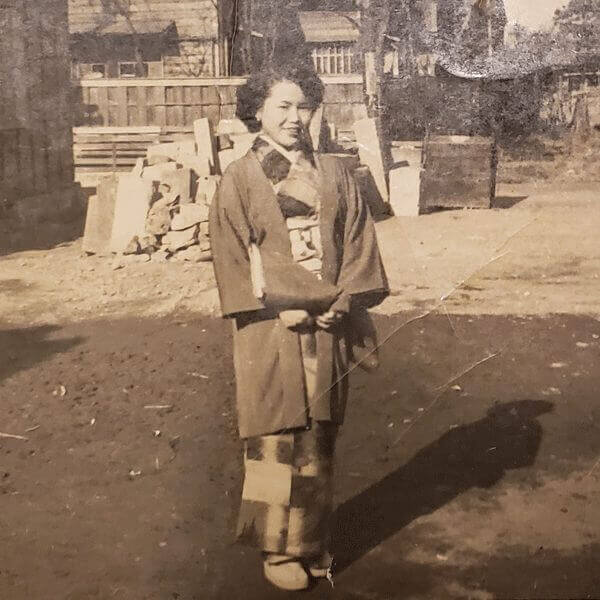

Mr. Iwawaki, a graduate of the respected Yokohama Business School, had what Setsuko described as ‘a good job’ working for an airplane parts company. He also had a serious spinal cord condition which gave him a humpback on the left side which was very painful. It also caused his death in 1940 when Setsuko was 11. To this day she remembers him as a gentleman whom she often accompanied to a local hot spring so he could get relief. Besides his advanced education, “my father was very westernized,” she notes. “He always wore Western clothes and shoes,” a preference he passed on to his sons, one of whom collected Western clothes and shoes as an adult. In fact, everyone in the family wore western clothes except Setsuko’s mother and grandmother. They both wore the traditional silk kimono except during the summer when it was too warm to wear silk comfortably. Then the two ladies wore cotton muumuus, Setsuko remembers.

Setsuko’s mother was also well-educated. Trained as a teacher, she preferred to be a stay-at-home Mom, her daughter says. Setsuko, as the oldest child, was expected to help her mother with all the responsibilities of a housewife and mother which she did until she got married herself in 1956. Asked if that was a common expectation for eldest daughters, she thinks it was. The same expectation was not laid on eldest sons, she notes with a wry smile. “Even my father didn’t do anything,” she adds.

While Setsuko’s father was still alive and working in the 1930s, the family was prosperous enough to own a telephone, rare for homes in Japan in those days. Setsuko remembers the neighbors coming over to ask if they could use it. Did they ever pay? She smiled and shook her head.

The family’s life changed in several ways after Mr. Iwawaki’s death. For a while, the family functioned financially as it had when the father was alive. Later, they moved out of downtown Tokyo to an area of the city farther east. Like eastern Contra Costa County, it combined city residences with small farms and orchards. Setsuko recalls crying about the move because “it was so far away.” In the end, it was a good move for the family because they were not near the horrific Tokyo Firebombing of March 1945, which, like a similar bombing by the Allies of Dresden, Germany, resulted in thousands of civilian deaths.

Second, Setsuko’s mother went to work in a factory. Third, the three younger brothers were sent to the north for their safety to live with their grandparents while Setsuko and her sister remained with their mother in the new home away from downtown Tokyo. Fourth: As was customary in Japanese families, Setsuko, as the first-born girl, had more responsibilities for the household than the younger children. Therefore, she could not accept an opportunity before Pearl Harbor to join a Western dance group that entertained the Japanese. “No,” her mother replied when asked. “You are the first (child in the family) so you have to help me.” It was what Setsuko calls “the old system.” The oldest daughter served as an assistant to the mother. “You don’t argue with Mother,” says the daughter. And fifth, Pearl Harbor happened in December 1941. As a result, life in Tokyo and throughout the country changed in many ways.

EDUCATION: Japanese schools were organized so that some students graduated in the 10th grade with working-class skills while those who were going on to university graduated two years later as in Australia and other countries.

Setsuko never lacked for jobs not only because of her personality and willingness to work hard but also because she was skilled with the abacus. In the days before computers and adding machines, the ancient abacus morphed into a variety of forms and uses. Her father used the Japanese soroban abacus at work. “He was a whiz with the abacus,” Setsuko says. She apparently inherited the skill so she took a class and became very adept. The strength of the soroban abacus is that it can be used for practical calculations even involving numbers of several digits as well as non-normal numbers such as 1.5 and ¾, according to Wikipedia. One of the jobs where she used the abacus was at the Tokyo Post Office/Insurance Company.

Another job was as an elevator operator in an 8-story building in downtown Tokyo taken over by the Americans. That job is significant because it inspired her to take English classes, and because that is where she met her future husband.

WAR – “In 1942, the War became very hard,” Setsuko says. The Doolittle Raid in 1942 was only the first air raid Setsuko experienced. As time passed, particularly in 1944 and 1945, the sirens began going off at night as well as during the day. The neighborhood of three homes constructed a sort of air-raid shelter. Since the water level was very close to the surface, the shelter couldn’t be underground. So, a neighbor constructed a heavy wooden wall with a roof attached and a bench along the wall. Dark material hung down from the roof on three sides. When the attacks began, the neighbors gathered beneath the roof on the bench by the wall. Fortunately, no bombs ever dropped really close to them, but it was frightening enough anyway.

The raids lasted approximately a half hour or so, she remembers. The number of raids and their destructive capacity increased in 1944 and especially 1945 when the US could use land-based bombers from the islands of Tinian and Okinawa. Before the end of the war, strafing became common forcing the family to huddle under the table in the house which had black curtains over the windows. “1945….that was a scary time,” Setsuko recalls.

She and her family were not touched by the March 10, 1945 midnight raid of B-29s dropping large numbers of incendiary (fire) bombs on the working-class neighborhoods of East Tokyo. An estimated 100,000 people were killed in six hours. Similar to the Dresden firebombing in Germany in 1945, the purpose was to destroy people’s homes and cause large loss of life in order to encourage the government to surrender. While 60 Japanese cities were firebombed with estimates that many hundreds of thousands of people were killed in 1945, it wasn’t until two atomic bombings in August 1945 that the emperor surrendered.

FOOD: There was rationing of course but her family obtained most of its food by “exchange” (bargaining) with nearby farmers. Although Setsuko had missed living downtown near the Imperial Palace, their new home was close to small farms where they could bargain with farmers for a variety of food. One farmer gave her mother a big bag of rice. She kept half of it and sold the remainder thus reaping more money for the family’s food needs. What was used for the exchange? One example is the beautiful silk kimonos Setsuko’s grandmother gave her each year for her birthday. Setsuko thinks about 10 or 12 of them were exchanged for food for the family.

The exchange disappeared after the war as many farmers were too old to farm and young people weren’t available for jobs in agriculture. It was replaced when the “the US gave a lot of food” to Japanese families including Setsuko’s which she says helped her recover from the negative feelings she had about America and Americans at the end of the war. The bombings and the hardship were one thing but the real issue for Setsuko was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

HIROSHIMA — The 75th anniversary of the atom bomb being dropped on Hiroshima occurred on Sunday, September 6, 2020, while we at Carlton Senior Living Pleasant Hill-Martinez were spending an unusually hot day inside the building. For Setsuko, however, it is an event deeply ingrained in her being. She was outside at home at 8:16 a.m. on Monday, September 6, 1945, when she saw the southern sky fill with a huge shiny vision in a variety of colors which soon disappeared. Because Hiroshima is 450 miles as the crow flies south of Tokyo, there was no sound to be heard and no mushroom cloud visible in Tokyo.

The news spread the next day that a new kind of bomb had been dropped, she recalls. The Japanese government was informed that unless it surrendered that day, another bomb would be dropped. When it didn’t heed the warning, the Nagasaki bomb was dropped. After that, the Emperor announced the surrender of the armed forces of the empire of Japan.

75 years later, Setsuko remembered vividly how angry she was at the time. “Everybody cried when the Emperor surrendered,” she says. Like many Japanese, she had been told “we would fight” to the bitter end. When she talks about it, she appears to have been ready to do just that herself.

However, she and other Japanese found out as time went on that Japan had been losing the war for years. But, she was asked, didn’t she know that the Americans were moving north across the Pacific from island to island including the Philippines and Okinawa? “No” she answers, adding that the Japanese government never told the population the truth about the last three years of World War II in the Pacific. She also openly admits to the wrongs of Japanese soldiers in China during the 1930s and in the Philippines and elsewhere in the 1940s.

According to an article in the 75th anniversary New York Times special edition, at the end of World War II, there were Americans and wrongs as well including the deliberate firebombing of working-class neighborhoods with no factories but many wooden homes and buildings. Several American airmen, now in their 90s, told the Times “we hated what we were doing.” The purpose of the raids was to get the Japanese government to surrender but it took two atom bombs to accomplish that.

Setsuko says that she honestly “hated the Americans” right after Hiroshima and the end of the war. When and how did that change? To begin with, as food became very scarce in the country because the farmers were aging with no one to replace them, the Americans stepped up and “gave us food.” Setsuko and her family were greatly helped by that. The Americans also were pleasant and helpful in other ways and provided lots of work opportunities which is how Setsuko ended up operating an elevator in an eight-story downtown Tokyo building and meeting in it the American man she would be married to for 63 years.

JOBS: Chicago-born Carroll Brockman was a young weatherman in 1952 when he was posted to the Air Force weather station in Tokyo. It was located on the top floor of an office building in downtown Tokyo commandeered along with two other even taller office buildings. Using the elevator each day, he was immediately attracted to the cute, vivacious Japanese operator who had learned English ‘on the job’ and by taking classes. Setsuko had a Japanese boyfriend at the time but he moved away at some point. After Carroll and Setsuko took a few rides in the elevator, he asked her out in the employee break room. He was 21, two years younger than Setsuko. She refused but he was persistent. She’d see him at the corner waiting for her at the end of the day. He would then walk her to the train station. He even came over to their home to ask her mother for permission to marry Setsuko. “No, you are not going to marry my daughter,” was Mother’s crisp reply. Setsuko only translated the “No.”

Carroll stayed in Japan until 1955. He went home, resigned from the Air Force, became a taxi driver in Chicago and did other jobs. In 1956, he rejoined the Air Force and was sent back to Japan. When stationed at Yohobe AFB near Tokyo, he reconnected with Setsuko. By this time, she says with a smile, “I’m thinkin’ he’s not such a bad guy.” They were married in 1956. He worked in the weather office and Setsuko, who never had a problem finding a job, worked in the base bookstore and as a cafeteria cashier. Their first child was born in Japan.

They went to America in 1959, living in a Chicago apartment where the heat was turned off at midnight in the winter so they woke up to ice in the apartment. Setsuko remembers the baby having to sleep between her parents. Her first household task was having to chip off an inch of ice covering the window when she got up. From there, they lived in Cincinnati where their second child was born and Setsuko became an American citizen.

For the next 30 years, the couple raised three children and lived much of the time in Japan where Carroll worked as a weather forecaster at two different U.S. airbases in the Tokyo area and later as a proofreader of the English language edition of Mainechi, one of the top four greater Tokyo daily newspapers. Her mother, whose feelings about Carroll had changed from suspicion to full approval, soon moved in with them and helped raise the grandchildren. Carroll’s last posting in the Air Force came in the 1970s when he and the family lived at Vandenburg Air Force Base in Southern California.

After retirement, they ended up in Sacramento where Carroll worked for the Stars and Stripes and Setsuko landed what must have been her favorite job considering how enthusiastically she talks about it. She worked in the IRS tax document repository in Sacramento. It was charged with keeping and distributing all kinds of federal income tax forms. That included not just current forms but also those going back to the beginning of the federal income tax in 1913. She holds both arms up far apart to show the size of the original tax form sheet. The repository staff made sure that the Fresno Internal Revenue Office had what it needed and also mailed whatever forms for whichever years businesses, law offices and the public needed.

Also in retirement, they made regular trips to Japan and traveled in the United States. They enjoyed going to Reno and Lake Tahoe and to some of the Indian casinos. Carroll would occasionally wake up in the morning and say to Setsuko, “Let’s go to Los Angeles (or elsewhere) for a few days” and they would.

Because the war canceled college for her, Setsuko feels so fortunate to have been able to take painting, crochet and ceramic classes as well as a variety of business classes at junior college and to have a great family. She and Carroll made sure their three girls could go to college without having to worry about paying for it.

The couple moved to Carlton Pleasant Hill – Martinez a few years ago, and after over 60 years of a happy marriage, Carroll passed away. Setsuko fondly sums up her marriage and her entire life as “Wonderful!” even with, or maybe even because of its challenges as well as its positives. Friendly Setsuko Iwawaki Brockman at 90+ is still what she always has been….what the Australians call “a bright spark.”